The Real Deal: Is the Mandela Effect real?

Flickr.com & Commons.wikimedia.org

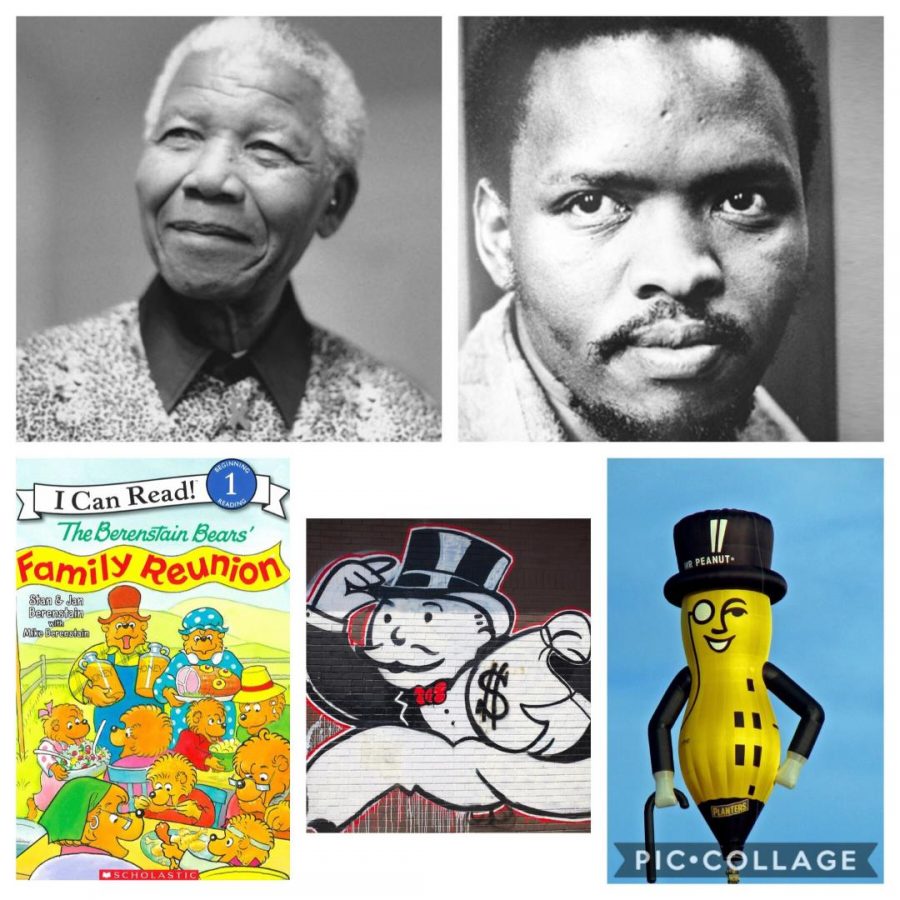

Picturing Nelson Mandela, Steve Biko, The Berenstain Bears, Rich Uncle Pennybags, and Mr. Peanut (from left to right, top to bottom), it is clear that there are some similarities between both South African activists, as well as between the Mr. Pennybags and Mr. Peanut. These similarities can cause the phenomenon of false memories, which are at the foundation of the Mandela Effect.

November 4, 2019

The Mandela Effect is defined as the phenomenon when a large group of people share a specific memory or memory of an event that did not actually occur. This brings in the theory of parallel realities, which are instances of reality that vary slightly from the reality that we currently live in. Hang in there, it will all be explained shortly.

The most famous example of the Mandela Effect is about who it was named after. Nelson Mandela, the first black president of South Africa, died in 2013, right? Well, a large group of people believed that he died in prison in the late 1980s. Though we know this is not true, how do we explain this large group of people who all agree on some of the details and the time that he died? Many people agree that he died in prison, remembering vividly the news clips of the funeral, the speech given by his widow, riots in cities, and other details. These people are mostly strangers, who never had contact with each other, yet they remember the same or very similar details of Mandela’s death.

Another popular example is the children’s book series The Berenstein Bears. However, it is actually spelled Berenstain, after the last names of the authors. These books were widely read, and many people agree with varying defenses that it was spelled with an E, not an A. Again, most of the people who agree on this do not know each other; it is a large, shared, false memory.

Another example is the man featured on the board game Monopoly, whose name is Rich Uncle Pennybags. Think of him. He is wearing a top hat, bowtie, an old-fashioned business suit, and a monocle, right? Mr. Pennybags never actually wore a monocle.

Many of those who believe in the Mandela Effect use it to justify the theory of alternate realities. How can so many people who are not connected in any way remember the same, incorrect details about varying things? Their answer? Junior Jackson Pruett agreed: “The thing is, it is all true. The false memories that I have been having are, I now realize, just me sliding between realities and receiving a glimpse into the multiverse.” We exist in slightly different realities that run parallel to each other. Most of the events and details of the realities are the same, but certain, specific things are only slightly different. This is where the realities diverge for a very small moment in time.

Though it sounds temptingly believable, it is not true. A phenomenon known as false memory is what doctors insist is what actually occurs, not alternate, parallel realities. A false memory is described as a recollection of an event that does not match historical records. In the case of the premature death of Nelson Mandela, there is evidence that the death of another prominent South African anti-apartheid activist, Steve Biko, in 1977 may have been confused with Mandela in some people’s memories. With The Berenstain Bears, people may have seen the title misspelled in newspapers or in notes from other kids or adults, and it simply manifested that way in their memories. The explanation for Rich Uncle Pennybags is that he looks somewhat similar to the Planters’ mascot, Mr. Peanut, who does wear a monocle.

So, the Mandela Effect is not real in the sense that it does not prove the parallel reality theory, but it does prove that false memories are very real. That is the Real Deal.